Nonlinear Programming#

Unless specific assumptions are made on the dynamics and cost structure, a DOCP is, in its most general form, a nonlinear mathematical program (commonly referred to as an NLP, not to be confused with Natural Language Processing). An NLP can be formulated as follows:

Where:

\(f: \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}\) is the objective function

\(\mathbf{g}: \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}^m\) represents inequality constraints

\(\mathbf{h}: \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}^\ell\) represents equality constraints

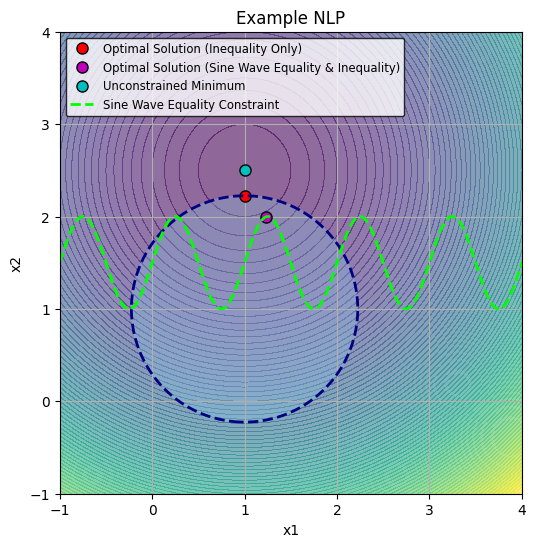

Unlike unconstrained optimization commonly used in deep learning, the optimality of a solution in constrained optimization must consider both the objective value and constraint feasibility. To illustrate this, consider the following problem, which includes both equality and inequality constraints:

In this example, the objective function \(f(x_1, x_2)\) is quadratic, the inequality constraint \(g(x_1, x_2)\) defines a circular feasible region centered at \((1, 1)\) with a radius of \(\sqrt{1.5}\) and the equality constraint \(h(x_1, x_2)\) requires \(x_2\) to lie on a sine wave function. The following code demonstrates the difference between the unconstrained, and constrained solutions to this problem.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.optimize import minimize

# Define the objective function

def objective(x):

return (x[0] - 1)**2 + (x[1] - 2.5)**2

# Define the inequality constraint function

def constraint(x):

return -(x[0] - 1)**2 - (x[1] - 1)**2 + 1.5

# Define the gradient of the objective function

def objective_gradient(x):

return np.array([2*(x[0] - 1), 2*(x[1] - 2.5)])

# Define the gradient of the inequality constraint function

def constraint_gradient(x):

return np.array([-2*(x[0] - 1), -2*(x[1] - 1)])

# Define the sine wave equality constraint function

def sine_wave_equality_constraint(x):

return x[1] - (0.5 * np.sin(2 * np.pi * x[0]) + 1.5)

# Define the gradient of the sine wave equality constraint function

def sine_wave_equality_constraint_gradient(x):

return np.array([-np.pi * np.cos(2 * np.pi * x[0]), 1])

# Define the constraints including the sine wave equality constraint

sine_wave_constraints = [{'type': 'ineq', 'fun': constraint, 'jac': constraint_gradient}, # Inequality constraint

{'type': 'eq', 'fun': sine_wave_equality_constraint, 'jac': sine_wave_equality_constraint_gradient}] # Sine wave equality constraint

# Define only the inequality constraint

inequality_constraints = [{'type': 'ineq', 'fun': constraint, 'jac': constraint_gradient}]

# Initial guess

x0 = [1.25, 1.5]

# Solve the optimization problem with the sine wave equality constraint

res_sine_wave_constraint = minimize(objective, x0, method='SLSQP', jac=objective_gradient,

constraints=sine_wave_constraints, options={'disp': False})

x_opt_sine_wave_constraint = res_sine_wave_constraint.x

# Solve the optimization problem with only the inequality constraint

res_inequality_only = minimize(objective, x0, method='SLSQP', jac=objective_gradient,

constraints=inequality_constraints, options={'disp': False})

x_opt_inequality_only = res_inequality_only.x

# Solve the unconstrained optimization problem for reference

res_unconstrained = minimize(objective, x0, method='SLSQP', jac=objective_gradient, options={'disp': False})

x_opt_unconstrained = res_unconstrained.x

# Generate data for visualization

x = np.linspace(-1, 4, 400)

y = np.linspace(-1, 4, 400)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(x, y)

Z = (X - 1)**2 + (Y - 2.5)**2 # Objective function values

constraint_values = (X - 1)**2 + (Y - 1)**2

# Data for sine wave constraint

x_sine = np.linspace(-1, 4, 400)

y_sine = 0.5 * np.sin(2 * np.pi * x_sine) + 1.5

# Visualization with Improved Color Scheme

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 6))

plt.contourf(X, Y, Z, levels=100, cmap='viridis', alpha=0.6) # Heatmap for the objective function

# Plot all the optimal points

plt.plot(x_opt_inequality_only[0], x_opt_inequality_only[1], 'ro', label='Optimal Solution (Inequality Only)', markersize=8, markeredgecolor='black')

plt.plot(x_opt_sine_wave_constraint[0], x_opt_sine_wave_constraint[1], 'mo', label='Optimal Solution (Sine Wave Equality & Inequality)', markersize=8, markeredgecolor='black')

plt.plot(x_opt_unconstrained[0], x_opt_unconstrained[1], 'co', label='Unconstrained Minimum', markersize=8, markeredgecolor='black')

# Adjust constraint boundary colors

plt.contour(X, Y, constraint_values, levels=[1.5], colors='navy', linewidths=2, linestyles='dashed')

plt.contourf(X, Y, constraint_values, levels=[0, 1.5], colors='skyblue', alpha=0.3)

# Plot the sine wave equality constraint with a high contrast color

plt.plot(x_sine, y_sine, 'lime', linestyle='--', linewidth=2, label='Sine Wave Equality Constraint')

plt.xlim([-1, 4])

plt.ylim([-1, 4])

plt.xlabel('x1')

plt.ylabel('x2')

plt.title('Example NLP')

plt.legend(loc='upper left', fontsize='small', edgecolor='black', fancybox=True)

plt.grid(True)

# Set the aspect ratio to be equal so the circle appears correctly

plt.gca().set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

plt.show()

Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions#

While this example is simple enough to convince ourselves visually of the solution to this particular problem, it falls short of providing us with actionable chracterization of what constitutes and optimal solution in general. The Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions provide us with an answer to this problem by generalizing the first-order optimality conditions in unconstrained optimization to problems involving both equality and inequality constraints. This result relies on the construction of an auxiliary function called the Lagrangian, defined as:

where \(\boldsymbol{\mu} \in \mathbb{R}^m\) and \(\boldsymbol{\lambda} \in \mathbb{R}^\ell\) are known as Lagrange multipliers. The first-order optimality conditions then state that if \(\mathbf{x}^*\), then there must exist corresponding Lagrange multipliers \(\boldsymbol{\mu}^*\) and \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^*\) such that:

Definition 8

The gradient of the Lagrangian with respect to \(\mathbf{x}\) must be zero at the optimal point (stationarity):

\[\nabla_x \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{x}^*, \boldsymbol{\mu}^*, \boldsymbol{\lambda}^*) = \nabla f(\mathbf{x}^*) + \sum_{i=1}^m \mu_i^* \nabla g_i(\mathbf{x}^*) + \sum_{j=1}^\ell \lambda_j^* \nabla h_j(\mathbf{x}^*) = \mathbf{0}\]In the case where we only have equality constraints, this means that the gradient of the objective and that of constraint are parallel to each other at the optimum but point in opposite directions.

A valid solution of a NLP is one which satisfies all the constraints (primal feasibility)

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{g}(\mathbf{x}^*) &\leq \mathbf{0}, \enspace \text{and} \enspace \mathbf{h}(\mathbf{x}^*) &= \mathbf{0} \end{aligned}\]Furthermore, the Lagrange multipliers for inequality constraints must be non-negative (dual feasibility)

\[\boldsymbol{\mu}^* \geq \mathbf{0}\]This condition stems from the fact that the inequality constraints can only push the solution in one direction.

Finally, for each inequality constraint, either the constraint is active (equality holds) or its corresponding Lagrange multiplier is zero at an optimal solution (complementary slackness)

\[\mu_i^* g_i(\mathbf{x}^*) = 0, \quad \forall i = 1,\ldots,m\]

Let’s now solve our example problem above, this time using Ipopt via the Pyomo interface so that we can access the Lagrange multipliers found by the solver.

Show code cell content

from pyomo.environ import *

from pyomo.opt import SolverFactory

from myst_nb import glue

import math

# Define the Pyomo model

model = ConcreteModel()

# Define the variables

model.x1 = Var(initialize=1.25)

model.x2 = Var(initialize=1.5)

# Define the objective function

def objective_rule(model):

return (model.x1 - 1)**2 + (model.x2 - 2.5)**2

model.obj = Objective(rule=objective_rule, sense=minimize)

# Define the inequality constraint (circle)

def inequality_constraint_rule(model):

return (model.x1 - 1)**2 + (model.x2 - 1)**2 <= 1.5

model.ineq_constraint = Constraint(rule=inequality_constraint_rule)

# Define the equality constraint (sine wave) using Pyomo's math functions

def equality_constraint_rule(model):

return model.x2 == 0.5 * sin(2 * math.pi * model.x1) + 1.5

model.eq_constraint = Constraint(rule=equality_constraint_rule)

# Create a suffix component to capture dual values

model.dual = Suffix(direction=Suffix.IMPORT)

# Create a solver

solver=SolverFactory('ipopt')

# Solve the problem

results = solver.solve(model, tee=False)

# Check if the solver found an optimal solution

if (results.solver.status == SolverStatus.ok and

results.solver.termination_condition == TerminationCondition.optimal):

# Print the results

print(f"x1: {value(model.x1)}")

print(f"x2: {value(model.x2)}")

# Print the objective value

print(f"Objective value: {value(model.obj)}")

# Print the Lagrange multipliers (dual values)

print("\nLagrange multipliers:")

for c in model.component_objects(Constraint, active=True):

for index in c:

print(f"{c.name}[{index}]: {model.dual[c[index]]}")

glue(f"{c.name}[{index}]", model.dual[c[index]], display=False)

else:

print("Solver did not find an optimal solution.")

print(f"Solver Status: {results.solver.status}")

print(f"Termination Condition: {results.solver.termination_condition}")

WARNING: Could not locate the 'ipopt' executable, which is required for solver

ipopt

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ApplicationError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[2], line 35

32 solver=SolverFactory('ipopt')

34 # Solve the problem

---> 35 results = solver.solve(model, tee=False)

37 # Check if the solver found an optimal solution

38 if (results.solver.status == SolverStatus.ok and

39 results.solver.termination_condition == TerminationCondition.optimal):

40

41 # Print the results

File ~/.local/pipx/venvs/jupyter-book/lib/python3.13/site-packages/pyomo/opt/base/solvers.py:534, in OptSolver.solve(self, *args, **kwds)

531 def solve(self, *args, **kwds):

532 """Solve the problem"""

--> 534 self.available(exception_flag=True)

535 #

536 # If the inputs are models, then validate that they have been

537 # constructed! Collect suffix names to try and import from solution.

538 #

539 from pyomo.core.base.block import BlockData

File ~/.local/pipx/venvs/jupyter-book/lib/python3.13/site-packages/pyomo/opt/solver/shellcmd.py:140, in SystemCallSolver.available(self, exception_flag)

138 if exception_flag:

139 msg = "No executable found for solver '%s'"

--> 140 raise ApplicationError(msg % self.name)

141 return False

142 return True

ApplicationError: No executable found for solver 'ipopt'

After running the code, we find that the Lagrange multiplier associated with the inequality constraint is approximately . This very small value, close to zero, suggests that the inequality constraint is not active at the optimal solution, meaning that the solution point lies inside the circle defined by this constraint. This can be verified visually in the figure above. As for the equality constraint, its corresponding Lagrange multiplier is and the fact that it’s non-zero indicates that this constraint is active at the optimal solution. In general when we find a Lagrange multiplier close to zero (like the one for the inequality constraint), it means that constraint is not “binding”—the optimal solution does not lie on the boundary defined by this constraint. In contrast, a non-zero Lagrange multiplier, such as the one for the equality constraint, indicates that the constraint is active and that any relaxation would directly affect the objective function’s value, as required by the stationarity condition.

Lagrange Multiplier Theorem#

The KKT conditions introduced above characterize the solution structure of constrained optimization problems with equality constraints. In this particular context, these conditions are referred to as the first-order optimality conditions, as part of the Lagrange multiplier theorem. Let’s just re-state them in that simpler setting:

Definition 9 (Lagrange Multiplier Theorem)

Consider the constrained optimization problem:

where \(\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n\), \(f: \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}\), and \(h_i: \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}\) for \(i = 1, \ldots, m\).

Assume that:

\(f\) and \(h_i\) are continuously differentiable functions.

The gradients \(\nabla h_i(\mathbf{x}^*)\) are linearly independent at the optimal point \(\mathbf{x}^*\).

Then, there exist unique Lagrange multipliers \(\lambda_i^* \in \mathbb{R}\), \(i = 1, \ldots, m\), such that the following first-order optimality conditions hold:

Stationarity: \(\nabla f(\mathbf{x}^*) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^* \nabla h_i(\mathbf{x}^*) = \mathbf{0}\)

Primal feasibility: \(h_i(\mathbf{x}^*) = 0\), for \(i = 1, \ldots, m\)

Note that both the stationarity and primal feasibility statements are simply saying that the derivative of the Lagrangian in either the primal or dual variables must be zero at an optimal constrained solution. In other words:

Letting \(\mathbf{F}(\mathbf{x}, \boldsymbol{\lambda})\) stand for \(\nabla_{\mathbf{x}, \boldsymbol{\lambda}} L(\mathbf{x}, \boldsymbol{\lambda})\), the Lagrange multipliers theorem tells us that an optimal primal-dual pair is actually a zero of that function \(\mathbf{F}\): the derivative of the Lagrangian. Therefore, we can use this observation to craft a solution method for solving equality constrained optimization using Newton’s method, which is a numerical procedure for finding zeros of a nonlinear function.

Newton’s Method#

Newton’s method is a numerical procedure for solving root-finding problems. These are nonlinear systems of equations of the form:

Find \(\mathbf{z}^* \in \mathbb{R}^n\) such that \(\mathbf{F}(\mathbf{z}^*) = \mathbf{0}\)

where \(\mathbf{F}: \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}^n\) is a continuously differentiable function. Newton’s method then consists in applying the following sequence of iterates:

where \(\mathbf{z}^k\) is the k-th iterate, and \(\nabla \mathbf{F}(\mathbf{z}^k)\) is the Jacobian matrix of \(\mathbf{F}\) evaluated at \(\mathbf{z}^k\).

Newton’s method exhibits local quadratic convergence: if the initial guess \(\mathbf{z}^0\) is sufficiently close to the true solution \(\mathbf{z}^*\), and \(\nabla \mathbf{F}(\mathbf{z}^*)\) is nonsingular, the method converges quadratically to \(\mathbf{z}^*\) [33]. However, the method is sensitive to the initial guess; if it’s too far from the desired solution, Newton’s method might fail to converge or converge to a different root. To mitigate this problem, a set of techniques known as numerical continuation methods [2] have been developed. These methods effectively enlarge the basin of attraction of Newton’s method by solving a sequence of related problems, progressing from an easy one to the target problem. This approach is reminiscent of several concepts in machine learning and statistical inference: curriculum learning in machine learning, where models are trained on increasingly complex data; tempering in Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) samplers, which gradually adjusts the target distribution to improve mixing; and modern diffusion models, which use a similar concept of gradually transforming noise into structured data.

Efficient Implementation of Newton’s Method#

Note that each step of Newton’s method involves computing the inverse of a Jacobian matrix. However, a cardinal rule in numerical linear algebra is to avoid computing matrix inverses explicitly: rarely, if ever, should there be a np.lindex.inv in your code. Instead, the numerically stable and computationally efficient approach is to solve a linear system of equations at each step.

Given the Newton’s method iterate:

We can reformulate this as a two-step procedure:

Solve the linear system: \(\underbrace{[\nabla \mathbf{F}(\mathbf{z}^k)]}_{\mathbf{A}} \Delta \mathbf{z}^k = -\mathbf{F}(\mathbf{z}^k)\)

Update: \(\mathbf{z}^{k+1} = \mathbf{z}^k + \Delta \mathbf{z}^k\)

The structure of the linear system in step 1 often allows for specialized solution methods. In the context of automatic differentiation, matrix-free linear solvers are particularly useful. These solvers can find a solution without explicitly forming the matrix A, requiring only the ability to evaluate matrix-vector or vector-matrix products. Typical examples of such methods include classical matrix-splitting methods (e.g., Richardson iteration) or conjugate gradient methods through sparse.linalg.cg for example. Another useful method is the Generalized Minimal Residual method (GMRES) implemented in SciPy via sparse.linalg.gmres, which is useful when facing non-symmetric and indefinite systems.

By inspecting the structure of matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) in the specific application where the function \(\mathbf{F}\) is the derivative of the Lagrangian, we will also uncover an important structure known as the KKT matrix. This structure will then allow us to derive a Quadratic Programming (QP) sub-problem as part of a larger iterative procedure for solving equality and inequality constrained problems via Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP).

Solving Equality Constrained Programs with Newton’s Method#

To solve equality-constrained optimization problems using Newton’s method, we begin by recognizing that the problem reduces to finding a zero of the function \(\mathbf{F}(\mathbf{z}) = \nabla_{\mathbf{x}, \boldsymbol{\lambda}} L(\mathbf{x}, \boldsymbol{\lambda})\). Here, \(\mathbf{F}\) represents the derivative of the Lagrangian function, and \(\mathbf{z} = (\mathbf{x}, \boldsymbol{\lambda})\) combines both the primal variables \(\mathbf{x}\) and the dual variables (Lagrange multipliers) \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}\). Explicitly, we have:

Newton’s method involves linearizing \(\mathbf{F}(\mathbf{z})\) around the current iterate \(\mathbf{z}^k = (\mathbf{x}^k, \boldsymbol{\lambda}^k)\) and then solving the resulting linear system. At each iteration \(k\), Newton’s method updates the current estimate by solving the linear system:

However, instead of explicitly inverting the Jacobian matrix \(\nabla \mathbf{F}(\mathbf{z}^k)\), we solve the linear system:

where \(\Delta \mathbf{z}^k = (\Delta \mathbf{x}^k, \Delta \boldsymbol{\lambda}^k)\) represents the Newton step for the primal and dual variables. Substituting the expression for \(\mathbf{F}(\mathbf{z})\) and its Jacobian, the system becomes:

The matrix on the left-hand side is known as the KKT matrix, as it stems from the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions for this optimization problem The solution of this system provides the updates \(\Delta \mathbf{x}^k\) and \(\Delta \boldsymbol{\lambda}^k\), which are then used to update the primal and dual variables:

Demonstration#

The following code demonstates how we can implement this idea in Jax. In this demonstration, we are minimizing a quadratic objective function subject to a single equality constraint, a problem formally stated as follows:

Geometrically speaking, the constraint \(h(x)\) describes a unit circle centered at the origin. To solve this problem using the method of Lagrange multipliers, we form the Lagrangian:

For this particular problem, it happens so that we can also find an analytical without even having to use Newton’s method. From the first-order optimality conditions, we obtain the following linear system of equations:

From the first two equations, we then get:

which we can substitute these into the 3rd constraint equation to obtain:

This value of the Lagrange multiplier can then be backsubstituted into the above equations to obtain \(x_1 = \frac{2}{\sqrt{5}}\) and \(x_2 = \frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\). We can verify numerically (and visually on the following graph) that the point \((2/\sqrt{5}, 1/\sqrt{5})\) is indeed the point on the unit circle closest to \((2, 1)\).

Show code cell source

import jax

import jax.numpy as jnp

from jax import grad, jit, jacfwd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Define the objective function and constraint

def f(x):

return (x[0] - 2)**2 + (x[1] - 1)**2

def g(x):

return x[0]**2 + x[1]**2 - 1

# Lagrangian

def L(x, lambda_):

return f(x) + lambda_ * g(x)

# Gradient and Hessian of Lagrangian

grad_L_x = jit(grad(L, argnums=0))

grad_L_lambda = jit(grad(L, argnums=1))

hess_L_xx = jit(jacfwd(grad_L_x, argnums=0))

hess_L_xlambda = jit(jacfwd(grad_L_x, argnums=1))

# Newton's method

@jit

def newton_step(x, lambda_):

grad_x = grad_L_x(x, lambda_)

grad_lambda = grad_L_lambda(x, lambda_)

hess_xx = hess_L_xx(x, lambda_)

hess_xlambda = hess_L_xlambda(x, lambda_).reshape(-1)

# Construct the full KKT matrix

kkt_matrix = jnp.block([

[hess_xx, hess_xlambda.reshape(-1, 1)],

[hess_xlambda, jnp.array([[0.0]])]

])

# Construct the right-hand side

rhs = jnp.concatenate([-grad_x, -jnp.array([grad_lambda])])

# Solve the KKT system

delta = jnp.linalg.solve(kkt_matrix, rhs)

return x + delta[:2], lambda_ + delta[2]

def solve_constrained_optimization(x0, lambda0, max_iter=100, tol=1e-6):

x, lambda_ = x0, lambda0

for i in range(max_iter):

x_new, lambda_new = newton_step(x, lambda_)

if jnp.linalg.norm(jnp.concatenate([x_new - x, jnp.array([lambda_new - lambda_])])) < tol:

break

x, lambda_ = x_new, lambda_new

return x, lambda_, i+1

# Analytical solution

def analytical_solution():

x1 = 2 / jnp.sqrt(5)

x2 = 1 / jnp.sqrt(5)

lambda_opt = jnp.sqrt(5) - 1

return jnp.array([x1, x2]), lambda_opt

# Solve the problem numerically

x0 = jnp.array([0.5, 0.5])

lambda0 = 0.0

x_opt_num, lambda_opt_num, iterations = solve_constrained_optimization(x0, lambda0)

# Compute analytical solution

x_opt_ana, lambda_opt_ana = analytical_solution()

# Verify the result

print("\nNumerical Solution:")

print(f"Constraint violation: {g(x_opt_num):.6f}")

print(f"Objective function value: {f(x_opt_num):.6f}")

print("\nAnalytical Solution:")

print(f"Constraint violation: {g(x_opt_ana):.6f}")

print(f"Objective function value: {f(x_opt_ana):.6f}")

print("\nComparison:")

x_diff = jnp.linalg.norm(x_opt_num - x_opt_ana)

lambda_diff = jnp.abs(lambda_opt_num - lambda_opt_ana)

print(f"Difference in x: {x_diff}")

print(f"Difference in lambda: {lambda_diff}")

# Precision test

rtol = 1e-5 # relative tolerance

atol = 1e-8 # absolute tolerance

x_close = jnp.allclose(x_opt_num, x_opt_ana, rtol=rtol, atol=atol)

lambda_close = jnp.isclose(lambda_opt_num, lambda_opt_ana, rtol=rtol, atol=atol)

print("\nPrecision Test:")

print(f"x values are close: {x_close}")

print(f"lambda values are close: {lambda_close}")

if x_close and lambda_close:

print("The numerical solution matches the analytical solution within the specified tolerance.")

else:

print("The numerical solution differs from the analytical solution more than the specified tolerance.")

# Visualize the result

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 10))

# Create a mesh for the contour plot

x1_range = jnp.linspace(-1.5, 2.5, 100)

x2_range = jnp.linspace(-1.5, 2.5, 100)

X1, X2 = jnp.meshgrid(x1_range, x2_range)

Z = jnp.array([[f(jnp.array([x1, x2])) for x1 in x1_range] for x2 in x2_range])

# Plot filled contours

contour = plt.contourf(X1, X2, Z, levels=50, cmap='viridis', alpha=0.7, extent=[-1.5, 2.5, -1.5, 2.5])

plt.colorbar(contour, label='Objective Function Value')

# Plot the constraint

theta = jnp.linspace(0, 2*jnp.pi, 100)

x1 = jnp.cos(theta)

x2 = jnp.sin(theta)

plt.plot(x1, x2, color='red', linewidth=2, label='Constraint')

# Plot the optimal points (numerical and analytical) and initial point

plt.scatter(x_opt_num[0], x_opt_num[1], color='red', s=100, edgecolor='white', linewidth=2, label='Numerical Optimal Point')

plt.scatter(x_opt_ana[0], x_opt_ana[1], color='blue', s=100, edgecolor='white', linewidth=2, label='Analytical Optimal Point')

plt.scatter(x0[0], x0[1], color='green', s=100, edgecolor='white', linewidth=2, label='Initial Point')

# Add labels and title

plt.xlabel('x1', fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel('x2', fontsize=12)

plt.title('Constrained Optimization: Numerical vs Analytical Solution', fontsize=14)

plt.legend(fontsize=10)

plt.grid(True, linestyle='--', alpha=0.7)

# Set the axis limits explicitly

plt.xlim(-1.5, 2.5)

plt.ylim(-1.5, 2.5)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

The SQP Approach: Taylor Expansion and Quadratic Approximation#

Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) tackles the problem of solving constrained programs by iteratively solving a sequence of simpler subproblems. Specifically, these subproblems are quadratic programs (QPs) that approximate the original problem around the current iterate by using a quadratic model of the objective function and a linear model of the constraints. Suppose we have the following optimization problem with equality constraints:

At each iteration \(k\), we approximate the objective function \(f(\mathbf{x})\) using a second-order Taylor expansion around the current iterate \(\mathbf{x}^k\). The standard Taylor expansion for \(f\) would be:

This expansion uses the Hessian of the objective function \(\nabla^2 f(\mathbf{x}^k)\) to capture the curvature of \(f\). However, in the context of constrained optimization, we also need to account for the effect of the constraints on the local behavior of the solution. If we were to use only \(\nabla^2 f(\mathbf{x}^k)\), we would not capture the influence of the constraints on the curvature of the feasible region. The resulting subproblem might then lead to steps that violate the constraints or are less effective in achieving convergence. The choice that we make instead is to use the Hessian of the Lagrangian, \(\nabla^2_{\mathbf{x}\mathbf{x}} L(\mathbf{x}^k, \boldsymbol{\lambda}^k)\), leading to the following quadratic model:

Similarly, the equality constraints \(\mathbf{h}(\mathbf{x})\) are linearized around \(\mathbf{x}^k\):

Combining these approximations, we obtain a Quadratic Programming (QP) subproblem, which approximates our original problem locally at \(\mathbf{x}^k\) but is easier to solve:

where \(\Delta \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}^k\). The QP subproblem solved at each iteration focuses on finding the optimal step direction \(\Delta \mathbf{x}\) for the primal variables. While solving this QP, we obtain not only the step \(\Delta \mathbf{x}\) but also the associated Lagrange multipliers for the QP subproblem, which correspond to an updated dual variable vector \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^{k+1}\). More specifically, after solving the QP, we use \(\Delta \mathbf{x}^k\) to update the primal variables:

Simultaneously, the Lagrange multipliers from the QP provide the updated dual variables \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^{k+1}\). We summarize the SQP algorithm in the following pseudo-code:

Algorithm 52 (Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP))

Input: Initial estimate \(\mathbf{x}^0\), initial Lagrange multipliers \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^0\), tolerance \(\epsilon > 0\).

Output: Solution \(\mathbf{x}^*\), Lagrange multipliers \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^*\).

Procedure:

Compute the QP Solution: Solve the QP subproblem to obtain \(\Delta \mathbf{x}^k\). The QP solver also provides the updated Lagrange multipliers \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^{k+1}\) associated with the constraints.

Update the Estimates: Update the primal variables:

\[ \mathbf{x}^{k+1} = \mathbf{x}^k + \Delta \mathbf{x}^k. \]Set the dual variables to the updated values \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^{k+1}\) from the QP solution.

Repeat Until Convergence: Continue iterating until \(\|\Delta \mathbf{x}^k\| < \epsilon\) and the KKT conditions are satisfied.

Connection to Newton’s Method in the Equality-Constrained Case#

The QP subproblem in SQP is directly related to applying Newton’s method for equality-constrained optimization. To see this, note that the KKT matrix of the QP subproblem is:

This is exactly the same linear system that have to solve when applying Newton’s method to the KKT conditions of the original program! Thus, solving the QP subproblem at each iteration of SQP is equivalent to taking a Newton step on the KKT conditions of the original nonlinear problem.

SQP for Inequality-Constrained Optimization#

So far, we’ve applied the ideas behind Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) to problems with only equality constraints. Now, let’s extend this framework to handle optimization problems that also include inequality constraints. Consider a general nonlinear optimization problem that includes both equality and inequality constraints:

As we did earlier, we approximate this problem by constructing a quadratic approximation to the objective and a linearization of the constraints. QP subproblem at each iteration is then formulated as:

where \(\Delta \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x}^k\) represents the step direction for the primal variables. The following pseudocode outlines the steps involved in applying SQP to a problem with both equality and inequality constraints:

Algorithm 53 (Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) with Inequality Constraints)

Input: Initial estimate \(\mathbf{x}^0\), initial multipliers \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^0, \boldsymbol{\nu}^0\), tolerance \(\epsilon > 0\).

Output: Solution \(\mathbf{x}^*\), Lagrange multipliers \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^*, \boldsymbol{\nu}^*\).

Procedure:

Initialization: Set \(k = 0\).

Repeat:

a. Construct the QP Subproblem: Formulate the QP subproblem using the current iterate \(\mathbf{x}^k\), \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^k\), and \(\boldsymbol{\nu}^k\):

\[\begin{split} \begin{aligned} \text{Minimize} \quad & \nabla f(\mathbf{x}^k)^T \Delta \mathbf{x} + \frac{1}{2} \Delta \mathbf{x}^T \nabla^2_{\mathbf{x}\mathbf{x}} L(\mathbf{x}^k, \boldsymbol{\lambda}^k, \boldsymbol{\nu}^k) \Delta \mathbf{x} \\ \text{subject to} \quad & \nabla \mathbf{g}(\mathbf{x}^k) \Delta \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{g}(\mathbf{x}^k) \leq \mathbf{0}, \\ & \nabla \mathbf{h}(\mathbf{x}^k) \Delta \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{h}(\mathbf{x}^k) = \mathbf{0}. \end{aligned} \end{split}\]b. Solve the QP Subproblem: Solve for \(\Delta \mathbf{x}^k\) and obtain the updated Lagrange multipliers \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^{k+1}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\nu}^{k+1}\).

c. Update the Estimates: Update the primal variables and multipliers:

\[ \mathbf{x}^{k+1} = \mathbf{x}^k + \Delta \mathbf{x}^k. \]d. Check for Convergence: If \(\|\Delta \mathbf{x}^k\| < \epsilon\) and the KKT conditions are satisfied, stop. Otherwise, set \(k = k + 1\) and repeat.

Return: \(\mathbf{x}^* = \mathbf{x}^{k+1}, \boldsymbol{\lambda}^* = \boldsymbol{\lambda}^{k+1}, \boldsymbol{\nu}^* = \boldsymbol{\nu}^{k+1}\).

Demonstration with JAX and CVXPy#

Consider the following equality and inequality-constrained problem:

This example builds on our previous one but adds a parabola-shaped inequality constraint. We require our solution to lie not only on the circle defining our equality constraint but also below the parabola. To solve the QP subproblem, we will be using the CVXPY package. While the Lagrangian and derivatives could be computed easily by hand, we use JAX for generality:

Show code cell source

import jax

import jax.numpy as jnp

from jax import grad, jit, jacfwd, hessian

import numpy as np

import cvxpy as cp

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Define the objective function and constraints

@jit

def f(x):

return (x[0] - 2)**2 + (x[1] - 1)**2

@jit

def g(x):

return jnp.array([x[0]**2 + x[1]**2 - 1])

@jit

def h(x):

return jnp.array([x[0]**2 - x[1]]) # Corrected inequality constraint: x[1] <= x[0]^2

# Compute gradients and Jacobians using JAX

grad_f = jit(grad(f))

hess_f = jit(hessian(f))

jac_g = jit(jacfwd(g))

jac_h = jit(jacfwd(h))

@jit

def lagrangian(x, lambda_, nu):

return f(x) + jnp.dot(lambda_, g(x)) + jnp.dot(nu, h(x))

hess_L = jit(hessian(lagrangian, argnums=0))

def solve_qp_subproblem(x, lambda_, nu):

n = len(x)

delta_x = cp.Variable(n)

# Convert JAX arrays to numpy for cvxpy

grad_f_np = np.array(grad_f(x))

hess_L_np = np.array(hess_L(x, lambda_, nu))

jac_g_np = np.array(jac_g(x))

jac_h_np = np.array(jac_h(x))

g_np = np.array(g(x))

h_np = np.array(h(x))

obj = cp.Minimize(grad_f_np.T @ delta_x + 0.5 * cp.quad_form(delta_x, hess_L_np))

constraints = [

jac_g_np @ delta_x + g_np == 0,

jac_h_np @ delta_x + h_np <= 0

]

prob = cp.Problem(obj, constraints)

prob.solve()

return delta_x.value, prob.constraints[0].dual_value, prob.constraints[1].dual_value

def sqp(x0, max_iter=100, tol=1e-6):

x = x0

lambda_ = jnp.zeros(1)

nu = jnp.zeros(1)

for i in range(max_iter):

delta_x, new_lambda, new_nu = solve_qp_subproblem(x, lambda_, nu)

if jnp.linalg.norm(delta_x) < tol:

break

x = x + delta_x

lambda_ = new_lambda

nu = new_nu

return x, lambda_, nu, i+1

# Initial point

x0 = jnp.array([0.5, 0.5])

# Solve using SQP

x_opt, lambda_opt, nu_opt, iterations = sqp(x0)

print(f"Optimal x: {x_opt}")

print(f"Optimal lambda: {lambda_opt}")

print(f"Optimal nu: {nu_opt}")

print(f"Iterations: {iterations}")

# Visualize the result

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 10))

# Create a mesh for the contour plot

x1_range = jnp.linspace(-1.5, 2.5, 100)

x2_range = jnp.linspace(-1.5, 2.5, 100)

X1, X2 = jnp.meshgrid(x1_range, x2_range)

Z = jnp.array([[f(jnp.array([x1, x2])) for x1 in x1_range] for x2 in x2_range])

# Plot filled contours

contour = plt.contourf(X1, X2, Z, levels=50, cmap='viridis', alpha=0.7)

plt.colorbar(contour, label='Objective Function Value')

# Plot the equality constraint

theta = jnp.linspace(0, 2*jnp.pi, 100)

x1_eq = jnp.cos(theta)

x2_eq = jnp.sin(theta)

plt.plot(x1_eq, x2_eq, color='red', linewidth=2, label='Equality Constraint')

# Plot the inequality constraint and shade the feasible region

x1_ineq = jnp.linspace(-1.5, 2.5, 100)

x2_ineq = x1_ineq**2

plt.plot(x1_ineq, x2_ineq, color='orange', linewidth=2, label='Inequality Constraint')

# Shade the feasible region for the inequality constraint

x2_lower = jnp.minimum(x2_ineq, 2.5)

plt.fill_between(x1_ineq, -1.5, x2_lower, color='gray', alpha=0.2, hatch='\\/...', label='Feasible Region')

# Plot the optimal and initial points

plt.scatter(x_opt[0], x_opt[1], color='red', s=100, edgecolor='white', linewidth=2, label='Optimal Point')

plt.scatter(x0[0], x0[1], color='green', s=100, edgecolor='white', linewidth=2, label='Initial Point')

# Add labels and title

plt.xlabel('x1', fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel('x2', fontsize=12)

plt.title('SQP for Inequality Constraints with CVXPY and JAX', fontsize=14)

plt.legend(fontsize=10, loc='upper center')

plt.grid(True, linestyle='--', alpha=0.7)

# Set the axis limits explicitly

plt.xlim(-1.5, 2.5)

plt.ylim(-1.5, 2.5)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Verify the result

print(f"\nEquality constraint violation: {g(x_opt)[0]:.6f}")

print(f"Inequality constraint violation: {h(x_opt)[0]:.6f}")

print(f"Objective function value: {f(x_opt):.6f}")

The Arrow-Hurwicz-Uzawa algorithm#

While the SQP method addresses constrained optimization problems by sequentially solving quadratic subproblems, an alternative approach emerges from viewing constrained optimization as a min-max problem. This perspective leads to a simpler algorithm, originally introduced by the Arrow-Hurwicz-Uzawa [3]. Consider the following general constrained optimization problem encompassing both equality and inequality constraints:

Using the Lagrangian function \(L(\mathbf{x}, \boldsymbol{\lambda}, \boldsymbol{\mu}) = f(\mathbf{x}) + \boldsymbol{\mu}^T \mathbf{g}(\mathbf{x}) + \boldsymbol{\lambda}^T \mathbf{h}(\mathbf{x})\), we can reformulate this problem as the following min-max problem:

The role of each component in this min-max structure can be understood as follows:

The outer minimization over \(\mathbf{x}\) finds the feasible point that minimizes the objective function \(f(\mathbf{x})\).

The maximization over \(\boldsymbol{\mu} \geq 0\) ensures that inequality constraints \(\mathbf{g}(\mathbf{x}) \leq \mathbf{0}\) are satisfied. If any inequality constraint is violated, the corresponding term in \(\boldsymbol{\mu}^T \mathbf{g}(\mathbf{x})\) can be made arbitrarily large by choosing a large enough \(\mu_i\).

The maximization over \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}\) ensures that equality constraints \(\mathbf{h}(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{0}\) are satisfied.

Using this observation, we can devise an algorithm which, like SQP, will update both the primal and dual variables at every step. But rather than using second-order optimization, we will simply use a first-order gradient update step: a descent step in the primal variable, and an ascent step in the dual one. The corresponding procedure, when implemented by gradient descent, is called Gradient Ascent Descent in the learning and optimization communities. In the case of equality constraints only, the algorithm looks like the following:

Algorithm 54 (Arrow-Hurwicz-Uzawa for equality constraints only)

Input: Initial guess \(\mathbf{x}^0\), \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^0\), step sizes \(\alpha\), \(\beta\) Output: Optimal \(\mathbf{x}^*\), \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^*\)

1: for \(k = 0, 1, 2, \ldots\) until convergence do

2: \(\mathbf{x}^{k+1} = \mathbf{x}^k - \alpha \nabla_{\mathbf{x}} L(\mathbf{x}^k, \boldsymbol{\lambda}^k)\) (Primal update)

3: \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^{k+1} = \boldsymbol{\lambda}^k + \beta \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\lambda}} L(\mathbf{x}^{k+1}, \boldsymbol{\lambda}^k)\) (Dual update)

4: end for

5: return \(\mathbf{x}^k\), \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^k\)

Now to account for the fact that the Lagrange multiplier needs to be non-negative for inequality constraints, we can use our previous idea from projected gradient descent for bound constraints and consider a projection, or clipping step to ensure that this condition is satisfied throughout. In this case, the algorithm looks like the following:

Algorithm 55 (Arrow-Hurwicz-Uzawa for equality and inequality constraints)

Input: Initial guess \(\mathbf{x}^0\), \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^0\), \(\boldsymbol{\mu}^0 \geq 0\), step sizes \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(\gamma\) Output: Optimal \(\mathbf{x}^*\), \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^*\), \(\boldsymbol{\mu}^*\)

1: for \(k = 0, 1, 2, \ldots\) until convergence do

2: \(\mathbf{x}^{k+1} = \mathbf{x}^k - \alpha \nabla_{\mathbf{x}} L(\mathbf{x}^k, \boldsymbol{\lambda}^k, \boldsymbol{\mu}^k)\) (Primal update)

3: \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^{k+1} = \boldsymbol{\lambda}^k + \beta \, \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\lambda}} L(\mathbf{x}^{k+1}, \boldsymbol{\lambda}^k, \boldsymbol{\mu}^k)\) (Dual update for equality constraints)

4: \(\boldsymbol{\mu}^{k+1} = [\boldsymbol{\mu}^k + \gamma \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\mu}} L(\mathbf{x}^{k+1}, \boldsymbol{\lambda}^k, \boldsymbol{\mu}^k)]_+\) (Dual update with clipping for inequality constraints)

5: end for

6: return \(\mathbf{x}^k\), \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^k\), \(\boldsymbol{\mu}^k\)

Here, \([\cdot]_+\) denotes the projection onto the non-negative orthant, ensuring that \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\) remains non-negative.

However, as it is widely known from the lessons of GAN (Generative Adversarial Network) training [18], Gradient Descent Ascent (GDA) can fail to converge or suffer from instability. The Arrow-Hurwicz-Uzawa algorithm, also known as the first-order Lagrangian method, is known to converge only locally, in the vicinity of an optimal primal-dual pair.

Show code cell source

import jax

import jax.numpy as jnp

from jax import grad, jit, value_and_grad

import optax

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Define the objective function and constraints

@jit

def f(x):

return (x[0] - 2)**2 + (x[1] - 1)**2

@jit

def g(x):

return jnp.array([x[0]**2 + x[1]**2 - 1])

@jit

def h(x):

return jnp.array([x[0]**2 - x[1]]) # Inequality constraint: x[1] <= x[0]^2

# Define the Lagrangian

@jit

def lagrangian(x, lambda_, mu):

return f(x) + jnp.dot(lambda_, g(x)) + jnp.dot(mu, h(x))

# Compute gradients of the Lagrangian

grad_L_x = jit(grad(lagrangian, argnums=0))

grad_L_lambda = jit(grad(lagrangian, argnums=1))

grad_L_mu = jit(grad(lagrangian, argnums=2))

# Define the Arrow-Hurwicz-Uzawa update step

@jit

def update(carry, t):

x, lambda_, mu, opt_state_x, opt_state_lambda, opt_state_mu = carry

# Compute gradients

grad_x = grad_L_x(x, lambda_, mu)

grad_lambda = grad_L_lambda(x, lambda_, mu)

grad_mu = grad_L_mu(x, lambda_, mu)

# Update primal variables (minimization)

updates_x, opt_state_x = optimizer_x.update(grad_x, opt_state_x)

x = optax.apply_updates(x, updates_x)

# Update dual variables (maximization)

updates_lambda, opt_state_lambda = optimizer_lambda.update(grad_lambda, opt_state_lambda)

lambda_ = optax.apply_updates(lambda_, -updates_lambda) # Positive update for maximization

updates_mu, opt_state_mu = optimizer_mu.update(grad_mu, opt_state_mu)

mu = optax.apply_updates(mu, -updates_mu) # Positive update for maximization

# Project mu onto the non-negative orthant

mu = jnp.maximum(mu, 0)

return (x, lambda_, mu, opt_state_x, opt_state_lambda, opt_state_mu), x

def arrow_hurwicz_uzawa(x0, lambda0, mu0, max_iter=1000):

# Initialize optimizers

global optimizer_x, optimizer_lambda, optimizer_mu

optimizer_x = optax.adam(learning_rate=0.01)

optimizer_lambda = optax.adam(learning_rate=0.01)

optimizer_mu = optax.adam(learning_rate=0.01)

opt_state_x = optimizer_x.init(x0)

opt_state_lambda = optimizer_lambda.init(lambda0)

opt_state_mu = optimizer_mu.init(mu0)

init_carry = (x0, lambda0, mu0, opt_state_x, opt_state_lambda, opt_state_mu)

# Use jax.lax.scan for the optimization loop

(x, lambda_, mu, _, _, _), trajectory = jax.lax.scan(update, init_carry, jnp.arange(max_iter))

return x, lambda_, mu, trajectory

# Initial point

x0 = jnp.array([0.5, 0.5])

lambda0 = jnp.zeros(1)

mu0 = jnp.zeros(1)

# Solve using Arrow-Hurwicz-Uzawa

x_opt, lambda_opt, mu_opt, trajectory = arrow_hurwicz_uzawa(x0, lambda0, mu0, max_iter=1000)

print(f"Final x: {x_opt}")

print(f"Final lambda: {lambda_opt}")

print(f"Final mu: {mu_opt}")

# Visualize the result

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 10))

# Create a mesh for the contour plot

x1_range = jnp.linspace(-1.5, 2.5, 100)

x2_range = jnp.linspace(-1.5, 2.5, 100)

X1, X2 = jnp.meshgrid(x1_range, x2_range)

Z = jnp.array([[f(jnp.array([x1, x2])) for x1 in x1_range] for x2 in x2_range])

# Plot filled contours

contour = plt.contourf(X1, X2, Z, levels=50, cmap='viridis', alpha=0.7)

plt.colorbar(contour, label='Objective Function Value')

# Plot the equality constraint

theta = jnp.linspace(0, 2*jnp.pi, 100)

x1_eq = jnp.cos(theta)

x2_eq = jnp.sin(theta)

plt.plot(x1_eq, x2_eq, color='red', linewidth=2, label='Equality Constraint')

# Plot the inequality constraint and shade the feasible region

x1_ineq = jnp.linspace(-1.5, 2.5, 100)

x2_ineq = x1_ineq**2

plt.plot(x1_ineq, x2_ineq, color='orange', linewidth=2, label='Inequality Constraint')

# Shade the feasible region for the inequality constraint

x2_lower = jnp.minimum(x2_ineq, 2.5)

plt.fill_between(x1_ineq, -1.5, x2_lower, color='gray', alpha=0.2, hatch='\\/...', label='Feasible Region')

# Plot the optimal and initial points

plt.scatter(x_opt[0], x_opt[1], color='red', s=100, edgecolor='white', linewidth=2, label='Final Point')

plt.scatter(x0[0], x0[1], color='green', s=100, edgecolor='white', linewidth=2, label='Initial Point')

# Plot the optimization trajectory using scatter plot

scatter = plt.scatter(trajectory[:, 0], trajectory[:, 1], c=jnp.arange(len(trajectory)),

cmap='cool', s=10, alpha=0.5)

plt.colorbar(scatter, label='Iteration')

# Add labels and title

plt.xlabel('x1', fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel('x2', fontsize=12)

plt.title('Arrow-Hurwicz-Uzawa Algorithm with JAX and Adam (Corrected Min/Max)', fontsize=14)

plt.legend(fontsize=10, loc='upper center', bbox_to_anchor=(0.5, -0.05), ncol=3)

plt.grid(True, linestyle='--', alpha=0.7)

# Set the axis limits explicitly

plt.xlim(-1.5, 2.5)

plt.ylim(-1.5, 2.5)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Verify the result

print(f"\nEquality constraint violation: {g(x_opt)[0]:.6f}")

print(f"Inequality constraint violation: {h(x_opt)[0]:.6f}")

print(f"Objective function value: {f(x_opt):.6f}")

Projected Gradient Descent#

The Arrow-Hurwicz-Uzawa algorithm provided a way to handle constraints through dual variables and a primal-dual update scheme. Another commonly used approach for constrained optimization is Projected Gradient Descent (PGD). The idea is simple: take a gradient descent step as if the problem were unconstrained, then project the result back onto the feasible set. Formally:

where \(\mathcal{P}_C\) is the projection onto the feasible set \(C\), \(\alpha\) is the step size, and \(f(\mathbf{x})\) is the objective function.

PGD is particularly effective when the projection is computationally cheap. A common example is box constraints (or bound constraints), where the feasible set is a hyperrectangle:

In this case, the projection reduces to an element-wise clipping operation:

For bound-constrained problems, PGD is almost as easy to implement as standard gradient descent because the projection step is just a clipping operation. For more general constraints, however, the projection may require solving a separate optimization problem, which can be as hard as the original task. Here is the algorithm for a problem of the form:

Algorithm 56 (Projected Gradient Descent for Bound Constraints)

Input: Initial point \(\mathbf{x}_0\), step size \(\alpha\), bounds \(\mathbf{x}_{\mathrm{lb}}, \mathbf{x}_{\mathrm{ub}}\), maximum iterations \(\max_\text{iter}\), tolerance \(\varepsilon\)

Initialize \(k = 0\)

While \(k < \max_\text{iter}\) and not converged:

Compute gradient: \(\mathbf{g}_k = \nabla f(\mathbf{x}_k)\)

Update: \(\mathbf{x}_{k+1} = \text{clip}(\mathbf{x}_k - \alpha \mathbf{g}_k,\; \mathbf{x}_{\mathrm{lb}}, \mathbf{x}_{\mathrm{ub}})\)

Check convergence: if \(\|\mathbf{x}_{k+1} - \mathbf{x}_k\| < \varepsilon\), stop

\(k = k + 1\)

Return \(\mathbf{x}_k\)

The clipping function is defined as:

Under mild conditions such as Lipschitz continuity of the gradient, PGD converges to a stationary point of the constrained problem. Its simplicity and low cost make it a common choice whenever the projection can be computed efficiently.