The previous chapter showed how to handle continuous action spaces in fitted Q-iteration by amortizing action selection with policy networks. Methods like NFQCA, DDPG, TD3, and SAC all learn both a Q-function and a policy, using the Q-function to guide policy improvement. This chapter explores a different approach: optimizing policies directly without maintaining explicit value functions.

Direct policy optimization offers several advantages. First, it naturally handles stochastic policies, which can be essential for partially observable environments or problems requiring explicit exploration. Second, it avoids the detour through value function approximation, which may introduce errors that compound during policy extraction. Third, for problems with simple policy classes but complex value landscapes, directly searching in policy space can be more efficient than searching in value space.

The foundation of policy gradient methods rests on computing gradients of expected returns with respect to policy parameters. This chapter develops the mathematical machinery needed for this computation, starting with general derivative estimation techniques from stochastic optimization, then specializing to reinforcement learning settings, and finally examining variance reduction methods that make these estimators practical.

Derivative Estimation for Stochastic Optimization¶

Consider optimizing an objective that involves an expectation:

For concreteness, consider a simple example where and . The derivative we seek is:

While we can compute this exactly for the Gaussian example, this is often impossible for more general problems. We might then be tempted to approximate our objective using samples:

Then differentiate this approximation:

However, this naive approach ignores that the samples themselves depend on . The correct derivative requires the product rule:

While the first term could be numerically integrated using Monte Carlo, the second one cannot as it is not in the form of an expectation.

To transform our objective so that the Monte Carlo estimator for the objective could be differentiated directly while ensuring that the resulting derivative is unbiased, there are two main solutions: a change of measure, or a change of variables.

The Likelihood Ratio Method¶

One solution comes from rewriting our objective using a proposal distribution that does not depend on :

Define the likelihood ratio , where we treat as a separate argument. The objective becomes:

When we differentiate , we take the partial derivative with respect to while holding fixed (since does not depend on ):

The partial derivative of with respect to (treating as fixed) is:

Now fix any reference parameter and choose the proposal distribution . This is a fixed distribution that does not change as varies. We simply evaluate the family at the specific point . With this choice, evaluating the gradient at gives . The gradient formula becomes:

Since is arbitrary, we can drop the subscript and write the score function estimator as:

The Reparameterization Trick¶

An alternative approach eliminates the -dependence in the sampling distribution by expressing through a deterministic transformation of the noise:

Therefore if we want to sample from some target distribution , we can do so by first sampling from a simple base distribution (like a standard normal) and then transforming those samples through a carefully chosen function . If is invertible, the change of variables formula tells us how these distributions relate:

For example, if we want to sample from any multivariate Gaussian distributions with covariance matrix and mean , it suffices to be able to sample from a standard normal noise and compute the linear transformation:

where is the matrix square root obtained via Cholesky decomposition. In the univariate case, this transformation is simply:

where is the standard deviation (square root of the variance).

Common Examples of Reparameterization¶

The Truncated Normal Distribution¶

When we need samples constrained to an interval , we can use the truncated normal distribution. To sample from it, we transform uniform noise through the inverse cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the standard normal:

Here:

is the CDF of the standard normal distribution

is its inverse (the quantile function)

is the error function

The resulting samples follow a normal distribution restricted to , with the density properly normalized over this interval.

The Kumaraswamy Distribution¶

When we need samples in the unit interval [0,1], a natural choice might be the Beta distribution. However, its inverse CDF doesn’t have a closed form. Instead, we can use the Kumaraswamy distribution as a convenient approximation, which allows for a simple reparameterization:

where:

are shape parameters that control the distribution

determines the concentration around 0

determines the concentration around 1

The distribution is similar to Beta(α,β) but with analytically tractable CDF and inverse CDF

The Kumaraswamy distribution has density:

The Gumbel-Softmax Distribution¶

When sampling from a categorical distribution with probabilities , one approach uses noise combined with the argmax of log-perturbed probabilities:

This approach, known in machine learning as the Gumbel-Max trick, relies on sampling Gumbel noise from uniform random variables through the transformation where . To see why this gives us samples from the categorical distribution, consider the probability of selecting category :

Since the difference of two Gumbel random variables follows a logistic distribution, , and these differences are independent for different (due to the independence of the original Gumbel variables), we can write:

The last equality requires some additional algebra to show, but follows from the fact that these probabilities must sum to 1 over all .

While we have shown that the Gumbel-Max trick gives us exact samples from a categorical distribution, the argmax operation isn’t differentiable. For stochastic optimization problems of the form:

we need to be differentiable with respect to . This leads us to consider a continuous relaxation where we replace the hard argmax with a temperature-controlled softmax:

As , this approximation approaches the argmax:

The resulting distribution over the probability simplex is called the Gumbel-Softmax (or Concrete) distribution. The temperature parameter controls the discreteness of our samples: smaller values give samples closer to one-hot vectors but with less stable gradients, while larger values give smoother gradients but more diffuse samples.

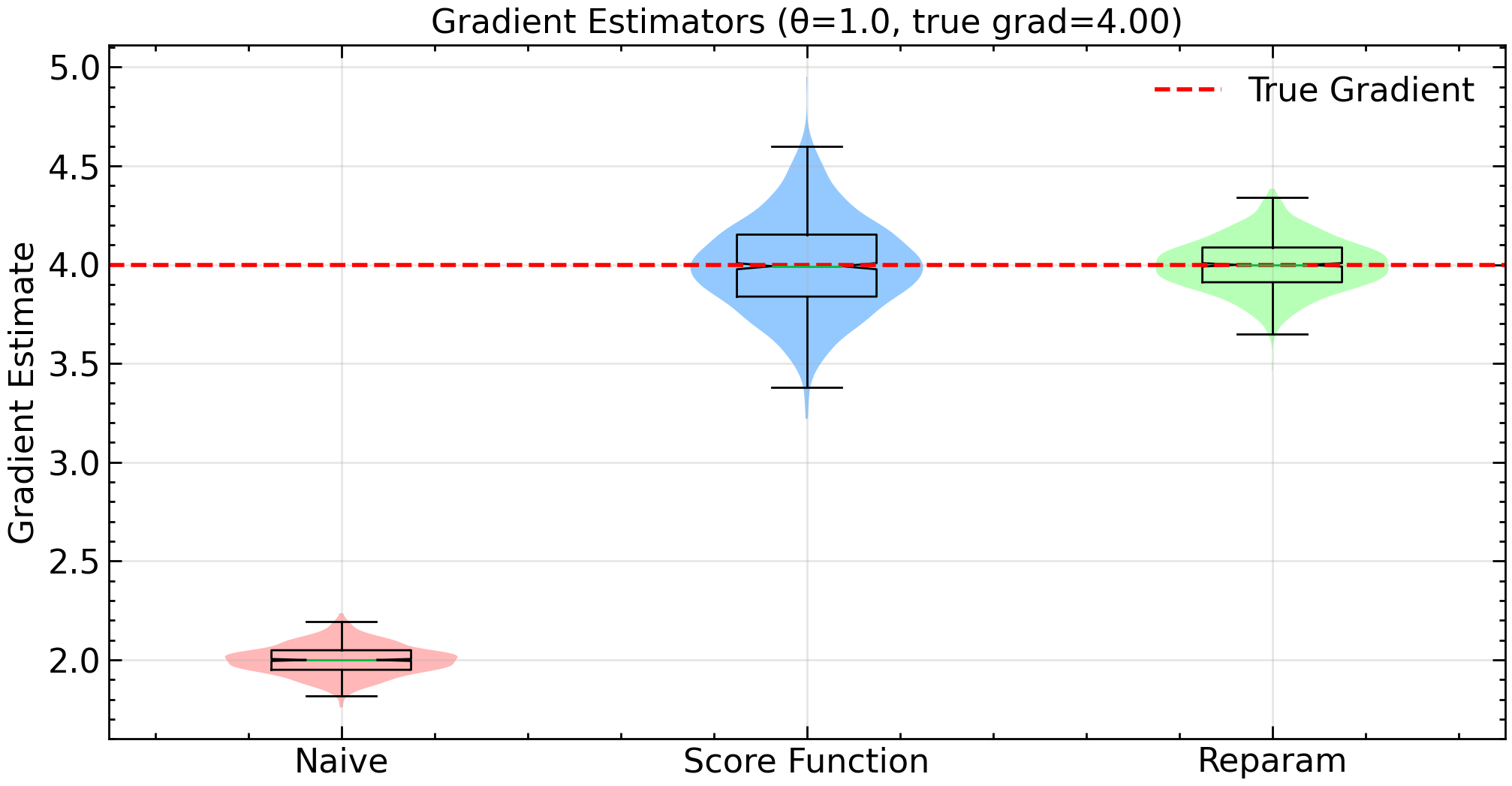

Numerical Analysis of Gradient Estimators¶

Let us examine the behavior of our three gradient estimators for the stochastic optimization objective:

To get an analytical expression for the derivative, first note that we can factor out to obtain where . By definition of the variance, we know that , which we can rearrange to . Since , we have and , therefore . This gives us:

Now differentiating with respect to using the product rule yields:

For concreteness, we fix and analyze samples drawn using Monte Carlo estimation with batch size 1000 and 1000 independent trials. Evaluating at gives us , which serves as our ground truth against which we compare our estimators:

First, we consider the naive estimator that incorrectly differentiates the Monte Carlo approximation:

For , we have and . We should therefore expect a bias of about -2 in our experiment.

Then we compute the score function estimator:

This estimator is unbiased with

Finally, through the reparameterization where , we obtain:

This estimator is also unbiased with .

Source

%config InlineBackend.figure_format = 'retina'

import jax

import jax.numpy as jnp

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Apply book style

try:

import scienceplots

plt.style.use(['science', 'notebook'])

except (ImportError, OSError):

pass # Use matplotlib defaults

key = jax.random.PRNGKey(0)

# Define the objective function f(x,θ) = x²θ where x ~ N(θ, 1)

def objective(x, theta):

return x**2 * theta

# Naive Monte Carlo gradient estimation

@jax.jit

def naive_gradient_batch(key, theta):

samples = jax.random.normal(key, (1000,)) + theta

# Use jax.grad on the objective with respect to theta

grad_fn = jax.grad(lambda t: jnp.mean(objective(samples, t)))

return grad_fn(theta)

# Score function estimator (REINFORCE)

@jax.jit

def score_function_batch(key, theta):

samples = jax.random.normal(key, (1000,)) + theta

# f(x,θ) * ∂logp(x|θ)/∂θ + ∂f(x,θ)/∂θ

# score function for N(θ,1) is (x-θ)

score = samples - theta

return jnp.mean(objective(samples, theta) * score + samples**2)

# Reparameterization gradient

@jax.jit

def reparam_gradient_batch(key, theta):

eps = jax.random.normal(key, (1000,))

# Use reparameterization x = θ + ε, ε ~ N(0,1)

grad_fn = jax.grad(lambda t: jnp.mean(objective(t + eps, t)))

return grad_fn(theta)

# Run trials

n_trials = 1000

theta = 1.0

true_grad = 1 + 3 * theta**2

keys = jax.random.split(key, n_trials)

naive_estimates = jnp.array([naive_gradient_batch(k, theta) for k in keys])

score_estimates = jnp.array([score_function_batch(k, theta) for k in keys])

reparam_estimates = jnp.array([reparam_gradient_batch(k, theta) for k in keys])

# Create violin plots with individual points

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

data = [naive_estimates, score_estimates, reparam_estimates]

colors = ['#ff9999', '#66b3ff', '#99ff99']

parts = plt.violinplot(data, showextrema=False)

for i, pc in enumerate(parts['bodies']):

pc.set_facecolor(colors[i])

pc.set_alpha(0.7)

# Add box plots

plt.boxplot(data, notch=True, showfliers=False)

# Add true gradient line

plt.axhline(y=true_grad, color='r', linestyle='--', label='True Gradient')

plt.xticks([1, 2, 3], ['Naive', 'Score Function', 'Reparam'])

plt.ylabel('Gradient Estimate')

plt.title(f'Gradient Estimators (θ={theta}, true grad={true_grad:.2f})')

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.legend()

# Print statistics

methods = {

'Naive': naive_estimates,

'Score Function': score_estimates,

'Reparameterization': reparam_estimates

}

for name, estimates in methods.items():

bias = jnp.mean(estimates) - true_grad

variance = jnp.var(estimates)

print(f"\n{name}:")

print(f"Mean: {jnp.mean(estimates):.6f}")

print(f"Bias: {bias:.6f}")

print(f"Variance: {variance:.6f}")

print(f"MSE: {bias**2 + variance:.6f}")

Naive:

Mean: 2.000417

Bias: -1.999583

Variance: 0.005933

MSE: 4.004266

Score Function:

Mean: 3.996162

Bias: -0.003838

Variance: 0.057295

MSE: 0.057309

Reparameterization:

Mean: 3.999940

Bias: -0.000060

Variance: 0.017459

MSE: 0.017459

The numerical experiments corroborate our theory. The naive estimator consistently underestimates the true gradient by 2.0, though it maintains a relatively small variance. This systematic bias would make it unsuitable for optimization despite its low variance. The score function estimator corrects this bias but introduces substantial variance. While unbiased, this estimator would require many samples to achieve reliable gradient estimates. Finally, the reparameterization trick achieves a much lower variance while remaining unbiased. While this experiment is for didactic purposes only, it reproduces what is commonly found in practice: that when applicable, the reparameterization estimator tends to perform better than the score function counterpart.

Score Function Methods in Reinforcement Learning¶

The score function estimator from the previous section applies directly to reinforcement learning. Since it requires only the ability to evaluate and differentiate , it works with any differentiable policy, including discrete action spaces where reparameterization is unavailable. It requires no model of the environment dynamics.

Let be the sum of undiscounted rewards in a trajectory . The stochastic optimization problem we face is to maximize:

where is a trajectory and is the total return. Applying the score function estimator, we get:

We have eliminated the need to know the transition probabilities in this estimator since the probability of a trajectory factorizes as:

Therefore, only the policy depends on . When taking the logarithm of this product, we get a sum where all the -independent terms vanish. The final estimator samples trajectories under the distribution and computes:

This is a direct application of the score function estimator. However, we rarely use this form in practice and instead make several improvements to further reduce the variance.

Leveraging Conditional Independence¶

Given the Markov property of the MDP, rewards for are conditionally independent of action given the history . This allows us to only need to consider future rewards when computing policy gradients.

The conditional independence assumption means that the term vanishes. To see this, factor the trajectory distribution as:

We can now re-write a single term of this summation as:

The inner expectation is zero because

The Monte Carlo estimator becomes:

This gives us the REINFORCE algorithm:

The benefit of this estimator compared to the naive one (which would weight each score function by the full trajectory return ) is that it generally has less variance. This variance reduction arises from the conditional independence structure we exploited: past rewards do not depend on future actions. More formally, this estimator is an instance of a variance reduction technique known as the Extended Conditional Monte Carlo Method.

The Surrogate Loss Perspective¶

The algorithm above computes a gradient estimate explicitly. In practice, implementations using automatic differentiation frameworks take a different approach: they define a surrogate loss whose gradient matches the REINFORCE estimator. For a single trajectory, consider:

where the returns and actions are treated as fixed constants (detached from the computation graph). Taking the gradient with respect to :

Minimizing this surrogate loss via gradient descent yields the same update as maximizing expected return via REINFORCE. The negative sign converts our maximization problem into a minimization suitable for standard optimizers.

This surrogate loss is not the expected return we are trying to maximize. It is a computational device that produces the correct gradient at the current parameter values. Several properties distinguish it from a true loss function:

It changes each iteration. The returns come from trajectories sampled under the current policy. After updating , we must collect new trajectories and construct a new surrogate loss.

Its value is not meaningful. Unlike supervised learning where the loss measures prediction error, the numerical value of has no direct interpretation. Only its gradient matters.

It is valid only locally. The surrogate loss provides the correct gradient only at the parameters used to collect the data. Moving far from those parameters invalidates the gradient estimate.

This perspective explains why policy gradient code often looks different from the pseudocode above. Instead of computing explicitly, implementations define the surrogate loss and call loss.backward():

# Surrogate loss implementation (single trajectory)

log_probs = [policy.log_prob(a_t, s_t) for s_t, a_t in trajectory]

returns = compute_returns(rewards)

surrogate_loss = -sum(lp * G for lp, G in zip(log_probs, returns))

surrogate_loss.backward() # computes REINFORCE gradient

optimizer.step()Variance Reduction via Control Variates¶

Recall that the REINFORCE gradient estimator, after leveraging conditional independence, takes the form:

This is a sum over trajectories and timesteps. The gradient contribution at timestep of trajectory is:

While unbiased, this estimator suffers from high variance because the return can vary significantly across trajectories even for the same state-action pair. The control variate method provides a principled way to reduce this variance.

General Control Variate Theory¶

For a general estimator of some quantity , and a control variate with known expectation , we can construct:

This remains unbiased since . The variance is:

The term is what enables variance reduction. If and are positively correlated, we can choose to make this term negative and large in magnitude, reducing the overall variance. However, the term grows quadratically with , so if we make too large, this quadratic term will eventually dominate and the variance will increase rather than decrease. The variance as a function of is a parabola opening upward, with a unique minimum. Setting gives:

This is the coefficient from ordinary least squares regression: we predict the estimator using the control variate as the predictor. Since , the linear model is , where is the OLS slope coefficient. The control variate estimator computes the residual: the part of that cannot be explained by .

Substituting into the variance formula yields:

where is the coefficient of determination from regressing on . The variance reduction is : the better predicts , the more variance we eliminate.

Application to REINFORCE¶

In the reinforcement learning setting, our REINFORCE gradient estimator is a sum over timesteps: where each represents the gradient contribution at timestep . We apply control variates separately to each term. Since , reducing the variance of each reduces the total variance, though we do not explicitly address the cross-timestep covariance terms.

For a given trajectory at state , the gradient contribution at time is:

This is the product of the score function and the return-to-go . We can subtract any state-dependent function from the return without introducing bias, as long as does not depend on . This is because:

where the last equality follows from the score function identity (38).

We can now define our control variate as:

where is a baseline function that depends only on the state. This satisfies . Our control variate estimator becomes:

The optimal baseline minimizes the variance. To find it, consider the scalar parameter case for simplicity. Write and . We want to minimize:

Since the mean does not depend on , minimizing the variance is equivalent to minimizing the second moment . Expanding and taking the derivative with respect to gives:

For vector-valued parameters , we minimize a scalar proxy such as the trace of the covariance matrix, which yields the same formula with in place of :

This is the exact optimal baseline: a weighted average of returns where the weights are the squared norms of the score function. In practice, we treat the squared norm as roughly constant across actions at a given state, which leads to the simpler and widely used choice:

With this approximation, the variance-reduced gradient contribution at timestep becomes:

The term in parentheses is exactly the advantage function: , where the Q-function is approximated by the Monte Carlo return . The full gradient estimate for a trajectory is then the sum over all timesteps:

In practice, we do not have access to the true value function and must learn it. Unlike the methods in the amortization chapter, where we learned value functions to approximate the optimal Q-function, here our goal is policy evaluation: estimating the value of the current policy . The same function approximation techniques apply, but we target rather than . The simplest approach is to regress from states to Monte Carlo returns, learning what Williams (1992) called a “baseline”:

When implementing this algorithm nowadays, we always use mini-batching to make full use of our GPUs. Therefore, a more representative variant for this algorithm would be:

The value function is trained by regressing states directly to their sampled Monte Carlo returns . Advantage normalization (step 2.5) is not part of the optimal baseline derivation but improves optimization in practice and is standard in modern implementations.

Generalized Advantage Estimation¶

The baseline construction gave us a gradient estimator of the form:

where is the Monte Carlo return from time . For each visited state-action pair , the term in parentheses

is a Monte Carlo estimate of the advantage . If the baseline equals the true value function, , then , so this estimator is unbiased.

However, as an estimator it has two limitations. First, it has high variance because depends on all future rewards. Second, it uses the value function only as a baseline, not as a predictor of long-term returns. We essentially discard the information in

GAE addresses these issues by constructing a family of estimators that interpolate between pure Monte Carlo and pure bootstrapping. A parameter controls the bias-variance tradeoff.

Decomposing the Monte Carlo Advantage¶

Fix a value function (not necessarily equal to ) and define the one-step residual:

Start from the Monte Carlo advantage and add and subtract :

Applying this decomposition recursively yields:

The Monte Carlo advantage is exactly the discounted sum of future residuals. This is an algebraic identity, not an approximation.

The sequence provides incremental corrections to the value function as we move forward in time. The term depends only on ; depends on , and so on. As increases, the corrections become more noisy (they depend on more random outcomes) and more sensitive to errors in the value function at later states. Although the full sum is unbiased when , it can have high variance and can be badly affected by approximation error in .

GAE as a Shrinkage Estimator¶

The decomposition above suggests a family of estimators that downweight residuals farther in the future. Let and define:

This is the generalized advantage estimator .

Two special cases illustrate the extremes. When , we recover the Monte Carlo advantage:

When , we keep only the immediate residual:

Intermediate values interpolate between these extremes. The influence of decays geometrically as . The parameter acts as a shrinkage parameter: small shrinks the estimator toward the one-step residual; large allows the estimator to behave more like the Monte Carlo advantage.

If is the true value function, then and for . In this case:

for all . When the value function is exact, GAE is unbiased regardless of ; changing only affects variance.

In practice, we approximate with a function approximator, and the residuals inherit approximation error. Distant residuals involve multiple applications of the approximate value function and are more contaminated by modeling error. Downweighting them (choosing ) introduces bias but can reduce variance and limit the impact of those errors.

Mixture of Multi-Step Estimators¶

Another perspective on GAE comes from multi-step returns. Define the -step return from time :

and the corresponding -step advantage estimator . Each uses rewards before bootstrapping; larger means more variance but less bootstrapping error.

The GAE estimator can be written as a geometric mixture:

GAE is a weighted average of the -step advantage estimators, with shorter horizons weighted more heavily when is small.

Using GAE in the Policy Gradient¶

Once we choose , we plug in place of in the policy gradient estimator:

We still use a control variate to reduce variance (the baseline ), but now we construct the advantage target by smoothing the sequence of residuals with a geometrically decaying kernel.

For the value function, it is convenient to define the -return:

When , reduces to the Monte Carlo return; when , it becomes the one-step bootstrapped target .

When , this reduces (up to advantage normalization) to the Monte Carlo baseline algorithm earlier in the chapter. When , advantages become the one-step residuals , and the -returns reduce to standard one-step bootstrapped targets.

Actor-Critic as the Limit¶

The case is particularly simple. The advantage becomes:

and the policy update reduces to:

while the value update becomes a standard one-step regression toward . This gives the online actor-critic algorithm:

This algorithm was derived by Sutton in his 1984 thesis as an “adaptive heuristic” for temporal credit assignment. In the language of this chapter, it is the member of the GAE family: it uses the most local residual as both the target for the value function and the advantage estimate for the policy gradient.

Likelihood Ratio Methods in Reinforcement Learning¶

The score function estimator from the previous section is a special case of the likelihood ratio method where the proposal distribution equals the target distribution. We now consider the general case where they differ.

Recall the likelihood ratio gradient estimator from the beginning of this chapter. For objective and any proposal distribution :

where is the likelihood ratio. The partial derivative holds because is treated as fixed, having been sampled from , which does not depend on .

In reinforcement learning, let be a trajectory, the return, the trajectory distribution under policy , and the trajectory distribution under some other policy . The gradient becomes:

where the trajectory likelihood ratio simplifies because transition probabilities cancel:

This product of ratios can become extremely large or small as grows, leading to high variance. The temporal structure provides some relief: since , future ratios for that do not affect the reward can be marginalized out. However, past ratios are still needed to correctly weight the probability of reaching state .

In practice, algorithms like PPO and TRPO make an additional approximation: they use only the per-step ratio rather than the cumulative product . This ignores the mismatch between the state distributions induced by the two policies. Combined with a baseline , the approximate estimator is:

This approximation corresponds to maximizing the importance-weighted surrogate objective:

where . Taking the gradient with respect to , only depends on (since trajectories are sampled from ):

The gradient of the ratio is:

Substituting back:

This matches equation (76). When , the ratios and we recover the score function estimator. The approximation error grows as the policies diverge, which motivates the trust region and clipping mechanisms discussed below.

Variance and the Dominance Condition¶

The ratio is well-behaved only when the two policies are similar. If assigns high probability to an action where assigns low probability, the ratio explodes. For example, if and , then , amplifying any noise in the advantage estimate.

Importance sampling also requires the dominance condition: the support of must be contained in the support of . If but , the ratio is undefined. Stochastic policies typically have full support, but the ratio can still become arbitrarily large as .

A common use case is to set , a previous version of the policy. This allows reusing data across multiple gradient steps: collect trajectories once, then update several times. But each update moves further from , making the ratios more extreme. Eventually, the gradient signal is dominated by a few samples with large weights.

Proximal Policy Optimization¶

The variance issues suggest a natural solution: keep the ratio close to 1 by ensuring the new policy stays close to the behavior policy. This keeps the importance-weighted surrogate from (77) well-behaved.

Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) formalizes this by adding a constraint on the KL divergence between the old and new policies:

The KL constraint ensures that the two distributions remain similar, which bounds how extreme the importance weights can become. This is a constrained optimization problem, and one could in principle apply standard methods such as projected gradient descent or augmented Lagrangian approaches (as discussed in the trajectory optimization chapter). TRPO takes a different approach: it uses a second-order Taylor approximation of the KL constraint around the current parameters and solves the resulting trust region subproblem using conjugate gradient methods. This involves computing the Fisher information matrix (the Hessian of the KL divergence), which adds computational overhead.

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) achieves similar behavior through a simpler mechanism: rather than constraining the distributions to be similar, it directly clips the ratio to prevent it from moving too far from 1. This is a construction-level guarantee rather than an optimization-level constraint.

From Trajectory Expectations to State-Action Averages¶

Before defining the PPO objective, we need to clarify the relationship between the trajectory-level surrogate (77) and the state-action level objective that PPO actually optimizes. The importance-weighted surrogate is defined as an expectation over trajectories:

We can rewrite this as an expectation over state-action pairs by introducing a sampling distribution. For a finite horizon , define the averaged time-marginal distribution:

where is the probability of being in state at time when following policy from the initial distribution. This is the uniform mixture over the time-indexed state-action distributions: we pick a timestep uniformly at random from , then sample from the joint distribution at that timestep.

With this definition, the trajectory expectation becomes:

The factor is just a constant that does not affect the optimization. This reformulation shows that the importance-weighted surrogate is equivalent to an expectation over state-action pairs drawn from the averaged time-marginal distribution. This is not a stationary distribution or a discounted visitation distribution, but the empirical mixture induced by the finite-horizon rollout procedure.

The Clipped Surrogate Objective¶

PPO replaces the linear importance-weighted term with a clipped version. For a state-action pair with advantage and importance ratio , define the per-sample clipped objective:

where is a hyperparameter (typically 0.1 or 0.2) and restricts to the interval .

The population-level PPO objective is then:

where the expectation is taken over the averaged time-marginal distribution (83) induced by .

In practice, we never compute this expectation exactly. Instead, we collect a batch of transitions by running and approximate the expectation with an empirical average:

This is the same plug-in approximation used in fitted Q-iteration: replace the unknown population distribution with the empirical distribution induced by the collected batch, then compute the sample average. The empirical surrogate is simply an expectation under . No assumptions about stationarity or discounted visitation are needed. We just average over the transitions we collected.

Intuition for the Clipping Mechanism¶

The operator in (85) selects the more pessimistic estimate. Consider the two cases:

Positive advantage (): The action is better than average, so we want to increase . The unclipped term increases with . The clipped term stops increasing once . Taking the minimum means we get the benefit of increasing only up to .

Negative advantage (): The action is worse than average, so we want to decrease . The unclipped term becomes less negative (improves) as decreases. The clipped term stops improving once . Taking the minimum means we get the benefit of decreasing only down to .

In both cases, the clipping removes the incentive to move the probability ratio beyond the interval . This keeps the new policy close to the old policy without explicitly computing or constraining the KL divergence.

The algorithm collects a batch of trajectories, then performs epochs of mini-batch updates on the same data. The empirical surrogate approximates the population objective (86) using samples from the averaged time-marginal distribution. The clipped objective ensures that even after multiple updates, the policy does not move too far from the policy that collected the data. The ratio is computed in log-space for numerical stability.

PPO has become one of the most widely used policy gradient algorithms due to its simplicity and robustness. Compared to TRPO, it avoids the computational overhead of constrained optimization while achieving similar sample efficiency. The clip parameter is the main hyperparameter controlling the trust region size: smaller values keep the policy closer to the behavior policy but may slow learning, while larger values allow faster updates but risk instability.

The Policy Gradient Theorem¶

The algorithms developed so far (REINFORCE, actor-critic, GAE, and PPO) all estimate policy gradients from sampled trajectories. We now establish the theoretical foundation for these estimators by deriving the policy gradient theorem in the discounted infinite-horizon setting.

Sutton et al. (1999) provided the original derivation. Here we present an alternative approach using the Implicit Function Theorem, which frames policy optimization as a bilevel problem:

subject to:

The Implicit Function Theorem states that if there is a solution to the problem , then we can “reparameterize” our problem as where is an implicit function of . If the Jacobian is invertible, then:

Here we made it clear in our notation that the derivative must be evaluated at root of . For the remaining of this derivation, we will drop this dependence to make notation more compact.

Applying this to our case with :

Then:

where we have defined the discounted state visitation distribution:

Recall the vector notation for MDPs from the dynamic programming chapter:

Taking derivatives with respect to gives:

Substituting back:

This is the policy gradient theorem, where is the discounted state visitation distribution and the term in parentheses is the state-action value function .

Normalized Discounted State Visitation Distribution¶

The discounted state visitation is not normalized. Therefore the expression we obtained above is not an expectation. However, we can transform it into one by normalizing by . Note that for any initial distribution :

Therefore, defining the normalized state distribution , we can write:

Now we have expressed the policy gradient theorem in terms of expectations under the normalized discounted state visitation distribution. But what does sampling from mean? Recall that . Using the Neumann series expansion (valid when , which holds for since is a stochastic matrix) we have:

We can then factor out the first term from this summation to obtain:

The balance equation:

shows that is a mixture distribution: with probability you draw a state from the initial distribution (reset), and with probability you follow the policy dynamics from the current state (continue). This interpretation directly connects to the geometric process: at each step you either terminate and resample from (with probability ) or continue following the policy (with probability ).

import numpy as np

def sample_from_discounted_visitation(

alpha,

policy,

transition_model,

gamma,

n_samples=1000

):

"""Sample states from the discounted visitation distribution.

Args:

alpha: Initial state distribution (vector of probabilities)

policy: Function (state -> action probabilities)

transition_model: Function (state, action -> next state probabilities)

gamma: Discount factor

n_samples: Number of states to sample

Returns:

Array of sampled states

"""

samples = []

n_states = len(alpha)

# Initialize state from alpha

current_state = np.random.choice(n_states, p=alpha)

for _ in range(n_samples):

samples.append(current_state)

# With probability (1-gamma): reset

if np.random.random() > gamma:

current_state = np.random.choice(n_states, p=alpha)

# With probability gamma: continue

else:

# Sample action from policy

action_probs = policy(current_state)

action = np.random.choice(len(action_probs), p=action_probs)

# Sample next state from transition model

next_state_probs = transition_model(current_state, action)

current_state = np.random.choice(n_states, p=next_state_probs)

return np.array(samples)

# Example usage for a simple 2-state MDP

alpha = np.array([0.7, 0.3]) # Initial distribution

policy = lambda s: np.array([0.8, 0.2]) # Dummy policy

transition_model = lambda s, a: np.array([0.9, 0.1]) # Dummy transitions

gamma = 0.9

samples = sample_from_discounted_visitation(alpha, policy, transition_model, gamma)

# Check empirical distribution

print("Empirical state distribution:")

print(np.bincount(samples) / len(samples))Empirical state distribution:

[0.85 0.15]

While the math shows that sampling from the discounted visitation distribution would give us unbiased policy gradient estimates, Thomas (2014) demonstrated that this implementation can be detrimental to performance in practice. The issue arises because terminating trajectories early (with probability ) reduces the effective amount of data we collect from each trajectory. This early termination weakens the learning signal, as many trajectories don’t reach meaningful terminal states or rewards.

Therefore, in practice, we typically sample complete trajectories from the undiscounted process (running the policy until natural termination or a fixed horizon) while still using in the advantage estimation. This approach preserves the full learning signal from each trajectory and has been empirically shown to lead to better performance.

This is one of several cases in RL where the theoretically optimal procedure differs from the best practical implementation.

The Actor-Critic Architecture¶

The policy gradient theorem shows that the gradient depends on the action-value function . In practice, we do not have access to the true -function and must estimate it. This leads to the actor-critic architecture: the actor maintains the policy , while the critic maintains an estimate of the value function.

This architecture traces back to Sutton’s 1984 thesis, where he proposed the Adaptive Heuristic Critic. The actor uses the critic’s value estimates to compute advantage estimates for the policy gradient, while the critic learns from the same trajectories generated by the actor. The algorithms we developed earlier (REINFORCE with baseline, GAE, and the one-step actor-critic) are all instances of this architecture.

We are simultaneously learning two functions that depend on each other, which creates a stability challenge. The actor’s gradient uses the critic’s estimates, but the critic is trained on data generated by the actor’s policy. If both change too quickly, the learning process can become unstable.

Konda (2002) analyzed this coupled learning problem and established convergence guarantees under a two-timescale condition: the critic must update faster than the actor. Intuitively, the critic needs to “track” the current policy’s value function before the actor uses those estimates to update. If the actor moves too fast, it uses stale or inaccurate value estimates, leading to poor gradient estimates.

In practice, this is implemented by using different learning rates: a larger learning rate for the critic and a smaller learning rate for the actor, with . Alternatively, one can perform multiple critic updates per actor update. The soft actor-critic algorithm discussed earlier in the amortization chapter follows this same principle, inheriting the actor-critic structure while incorporating entropy regularization and learning Q-functions directly.

The actor-critic architecture also connects to the bilevel optimization perspective of the policy gradient theorem: the outer problem optimizes the policy, while the inner problem solves for the value function given that policy. The two-timescale condition ensures that the inner problem is approximately solved before taking a step on the outer problem.

Reparameterization Methods in Reinforcement Learning¶

When dynamics are known or can be learned, reparameterization provides an alternative to score function methods. By expressing actions and state transitions as deterministic functions of noise, we can backpropagate through trajectories to compute policy gradients with lower variance than score function estimators.

Stochastic Value Gradients¶

The reparameterization trick requires that we can express our random variable as a deterministic function of noise. In reinforcement learning, this applies naturally when we have a learned model of the dynamics. Consider a stochastic policy that we can reparameterize as where , and a dynamics model where represents environment stochasticity. Both transformations are deterministic given the noise variables.

With these reparameterizations, we can write an -step return as a differentiable function of the noise:

where and for . The objective becomes:

We can now apply the reparameterization gradient estimator:

This gradient can be computed by automatic differentiation through the sequence of policy and model evaluations. The computation requires backpropagating through steps of model rollouts, which becomes expensive for large but avoids the high variance of score function estimators.

The Stochastic Value Gradients (SVG) framework Heess et al., 2015 uses this approach while introducing a hybrid objective that combines model rollouts with value function bootstrapping:

The terminal value function approximates the value beyond horizon , allowing shorter rollouts while still capturing long-term value. This creates a spectrum of algorithms parameterized by .

SVG(0): Model-Free Reparameterization¶

When , the objective collapses to:

No model is required. We simply differentiate the critic with respect to actions sampled from the reparameterized policy. This is the approach used in DDPG Lillicrap et al., 2015 (with a deterministic policy where is absent) and SAC Haarnoja et al., 2018 (where produces the stochastic component). The gradient is:

This requires only that the critic be differentiable with respect to actions, not a learned dynamics model. All bias comes from errors in the value function approximation.

SVG(1) to SVG(): Model-Based Rollouts¶

For , we unroll a learned dynamics model for steps before bootstrapping with the critic. Consider SVG(1):

where is the next state predicted by the model. The gradient now flows through both the reward and the model transition. Increasing propagates reward information more directly through the model rollout, reducing reliance on the critic. However, model errors compound over the horizon. If the model is inaccurate, longer rollouts can degrade performance.

SVG(): Pure Model-Based Optimization¶

As , we eliminate the critic entirely:

This is pure model-based policy optimization, differentiating through the entire trajectory. Approaches like PILCO Deisenroth & Rasmussen, 2011 and Dreamer Hafner et al., 2019 operate in this regime. With an accurate model, this provides the most direct gradient signal. The tradeoff is computational: backpropagating through hundreds of time steps is expensive, and gradient magnitudes can explode or vanish over long horizons.

The choice of reflects a fundamental bias-variance tradeoff. Small relies on the critic for long-term value estimation, inheriting its approximation errors. Large relies on the model, accumulating its prediction errors. In practice, intermediate values like or often work well when combined with a reasonably accurate learned model.

Noise Inference for Off-Policy Learning¶

A subtle issue arises when combining reparameterization with experience replay. SVG naturally supports off-policy learning: states can be sampled from a replay buffer rather than the current policy. However, reparameterization requires the noise variables that generated each action.

For on-policy data, we can simply store alongside each transition . For off-policy data collected under a different policy, the noise is unknown. To apply reparameterization gradients to such data, we must infer the noise that would have produced the observed action under the current policy.

For invertible policies, this is straightforward. If with , and the policy takes the form (as in a Gaussian policy), we can recover the noise exactly:

This recovered can then be used for gradient computation. However, this introduces a subtle dependence: the inferred depends on the current policy parameters , not just the data. As the policy changes during training, the same action corresponds to different noise values.

For dynamics noise , the situation is more complex. If we have a probabilistic model and observe the actual next state , we could in principle infer . In practice, environment stochasticity is often treated as irreducible: we cannot replay the exact same noise realization. SVG handles this by either: (1) using deterministic models and ignoring environment stochasticity, (2) re-simulating from the model rather than using observed next states, or (3) using importance weighting to correct for the distribution mismatch.

The noise inference perspective connects reparameterization gradients to the broader question of credit assignment in RL. By explicitly tracking which noise realizations led to which outcomes, we can more precisely attribute value to policy parameters rather than to lucky or unlucky samples.

When dynamics are deterministic or can be accurately reparameterized, SVG-style methods offer an efficient alternative to the score function methods developed in the previous section. However, many reinforcement learning problems involve unknown dynamics or dynamics that resist accurate modeling. In those settings, score function methods remain the primary tool since they require only the ability to sample trajectories under the policy.

Summary¶

This chapter developed the mathematical foundations for policy gradient methods. Starting from general derivative estimation techniques in stochastic optimization, we saw two main approaches: the likelihood ratio (score function) method and the reparameterization trick. While the reparameterization trick typically offers lower variance, it requires that the sampling distribution be reparameterizable, making it inapplicable to discrete actions or environments with complex dynamics.

For reinforcement learning, the score function estimator provides a model-free gradient that depends only on the policy parametrization, not the transition dynamics. Through variance reduction techniques (leveraging conditional independence, using control variates, and the Generalized Advantage Estimator), we can make these gradients practical for learning. The likelihood ratio perspective then led to importance-weighted surrogates and PPO’s clipped objective for stable off-policy updates.

We also established the policy gradient theorem, which provides the theoretical foundation for these estimators in the discounted infinite-horizon setting. The actor-critic architecture emerges from approximating the value function that appears in this theorem, with the two-timescale condition ensuring stable learning.

When dynamics models are available, reparameterization through Stochastic Value Gradients offers lower-variance alternatives. SVG(0) recovers actor-critic methods like DDPG and SAC, while SVG() represents pure model-based optimization through differentiable simulation.

- Williams, R. J. (1992). Simple Statistical Gradient-Following Algorithms for Connectionist Reinforcement Learning. Machine Learning, 8(3), 229–256. 10.1007/BF00992696

- Sutton, R. S., McAllester, D., Singh, S., & Mansour, Y. (1999). Policy Gradient Methods for Reinforcement Learning with Function Approximation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 12, 1057–1063.

- Konda, V. R. (2002). Actor-Critic Algorithms [Phdthesis]. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Heess, N., Wayne, G., Silver, D., Lillicrap, T., Erez, T., & Tassa, Y. (2015). Learning Continuous Control Policies by Stochastic Value Gradients. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 28, 2944–2952.

- Lillicrap, T. P., Hunt, J. J., Pritzel, A., Heess, N., Erez, T., Tassa, Y., Silver, D., & Wierstra, D. (2015). Continuous Control with Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv Preprint arXiv:1509.02971.

- Haarnoja, T., Zhou, A., Abbeel, P., & Levine, S. (2018). Soft actor-critic: Off-policy maximum entropy deep reinforcement learning with a stochastic actor. Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 1861–1870.

- Deisenroth, M. P., & Rasmussen, C. E. (2011). PILCO: A Model-Based and Data-Efficient Approach to Policy Search. Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 465–472.

- Hafner, D., Lillicrap, T., Ba, J., & Norouzi, M. (2019). Dream to Control: Learning Behaviors by Latent Imagination. arXiv Preprint arXiv:1912.01603.